Oil company records from 1960s reveal patents to reduce CO2 emissions in cars

ExxonMobil and others pursued research into technologies, yet blocked government efforts to fight climate change for more than 50 years, findings show

The forerunners of ExxonMobil patented technologies for electric cars and low emissions vehicles as early as 1963 – even as the oil industry lobby tried to squash government funding for such research, according to a trove of newly discovered records.

Patent records reveal oil companies actively pursued research into technologies to cut carbon dioxide emissions that cause climate change from the 1960s – including early versions of the batteries now deployed to power electric cars such as the Tesla.

Scientists for the companies patented technologies to strip carbon dioxide out of exhaust pipes, and improve engine efficiency, as well as fuel cells. They also conducted research into countering the rise in carbon dioxide emissions – including manipulating the weather.

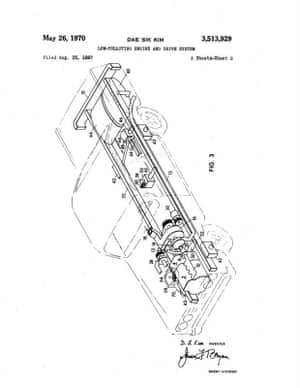

Esso, one of the precursors of ExxonMobil, obtained at least three fuel cell patents in the 1960s and another for a low-polluting vehicle in 1970, according to the records. Other oil companies such as Phillips and Shell also patented technologies for more efficient uses of fuel.

However, the American Petroleum Institute, the main oil lobby, opposed government funding of research into electric cars and low emissions vehicles, telling Congress in 1967: “We take exception to the basic assumption that clean air can be achieved only by finding an alternative to the internal combustion engine.”

And ExxonMobil funded a disinformation campaigned aimed at discrediting scientists and blocking government efforts to fight climate change for more than 50 years, before publicly disavowing climate denial in 2008.

The patent records were among a new trove of documents published on Thursday by the Center for International Environmental Law, and deepen the legal and public relations challenge for Exxon.

“What we saw was an array of patent technologies that demonstrated that these companies had the technologies they needed and could have commercialised to help address the problem of C02 pollution,” said Carroll Muffett, president of the Ciel. “They then turned to Congress and said you don’t need to invest in electrical vehicle research because the research is ongoing and it’s robust.”

The findings echo those in the documentary Who Killed the Electric Car?, which explored the deliberate destruction of GM’s first electric vehicles.

Alan Jeffers, an Exxon spokesman, insisted he could not comment directly on the documents as he was unable to access the Center for International Environmental law website on which they were published on Thursday morning.

In an emailed statement, Jeffers said: “The Guardian gave us only a few hours to comment on documents from four decades ago.”

Jeffers went on: “This further illustrates the Guardian’s well-established bias on climate change issues which has been demonstrated previously through its keep it in the ground campaign.”

He said the company believed the risks of climate change were real, was researching lower emission technologies, and engaged in “constructive dialogue” with policy makers about energy and climate change.

Researchers discovered more than 20 such patents filed by oil companies from as early as the 1940s for technologies that could help in the development of electric cars.

However, Ron Dunlop, president of Sun Oil and API chairman, told a joint hearing of the commerce committee in 1967 that government funding of research into electric cars would be misplaced – because the oil companies were so advanced in their research of cleaner cars. “We in the petroleum industry are convinced that by the time a practical electric car can be mass produced and marketed, it will not enjoy any meaningful advantage from an air pollution standpoint,” he told Congress. “Emissions from internal-combustion engines will have long since been controlled.”

Muffett said the findings were the result of three years of research and were not exhaustive.

“The question is what did they do to try to commercialise these technologies, knowing what they did about climate change,” he went on.

The revelations, the second set of documents released by Muffett’s organisation, reinforce charges by campaigners that Exxon was well aware that the burning of fossil fuels was a main driver of climate change – despite its public posture of doubt.

In addition to the technologies with potential for electric cars, Exxon and other oil companies were actively researching methods to cut emissions of carbon dioxide – the main greenhouse gas.

In another historic document that surfaced last month, a Canadian subsidiary of Exxon admitted the company had the technology to cut carbon emissions in half. However, the corporate memo dating from 1977 said it would be prohibitively expensive – doubling the cost of electricity generation, according to the documents obtained by Desmog blog.

New York and 17 other attorneys general, including DC and the US Virgin Islands, are investigating whether the oil company lied to investors and the public about the threat of climate change.

Campaigners plan to further turn up the heat on the company next week when Exxon holds its annual shareholder meeting in Dallas.

Campaigners have argued for more than a decade that Exxon bankrolled a network of front groups and conservative think tanks aimed at discrediting well-established science – confusing the public and delaying governments efforts to cut the greenhouse gas emissions responsible for warming.

Those efforts to put Exxon on the spot gathered pace after Inside Climate News and the Los Angeles Times reported that the company’s own scientists knew as early as the 1970s that greenhouse gases caused climate change.

The attorney general of the US Virgin Islands has subpoenaed Exxon to turn over email, documents and statements over the last decades.

Exxon has dismissed the investigations as politically motivated.

However, the company has reversed its opposition to fuel cell technology. Earlier this month, the company announced it had been conducting a joint research effort on fuel cell power plants with FuelCell.

The initiative, which got underway in 2011, aims to route the carbon dioxide from fossil fuel burning power plants into fuel cells, producing low emissions electricity. The company has estimated it can cut 90% of carbon dioxide emissions.

“At ExxonMobil, we share the view that the risks of climate change are serious and warrant thoughtful action,” Rex Tillerson, Exxon’s chief executive, told the US Energy Association after receiving its annual award.